Pr. Robert DengAXA Chair in Cybersecurity, School of Information Systems, Singapore Management University

October 20, 2017

Why we need to improve cloud computing’s security

Do you often use Facebook? How about Snapchat, Gmail, Dropbox, Slack, Google Drive, Spotify or Minecraft? Perhaps all of them? Bottom line, if you use an online social network, e-mail program, data storage service or a music platform, you are almost certainly using cloud computing.

3 minutes

Original Content: The Conversation, in partnership with the AXA Research Fund

Cloud computing is way of giving access to shared resources such as computer networks, servers, storage, applications and services. Individuals and organisations can place their data on the cloud and enjoy unlimited storage free or at a relatively low cost. It also allows services such as email to be offloaded, reducing companies’ development and maintenance costs.

Data breaches happen every day

Despite the tremendous benefits of cloud computing, the security and privacy of data are probably the biggest concerns that individuals and organisational users have. Current efforts to protect users’ data include measure such as firewalls, virtualisation (running multiple operating systems or applications simultaneously) and even regulatory policies, yet often users are required to provide information to service providers in the clear

– means plain-text data without any protection.

Moreover, because cloud-computing software and hardware are anything but bug-free, sensitive information may be exposed to other users, applications and third parties. In fact, cloud data breaches happen every day.

The cyber-security website Csoonline.com compiled a list of 16 of the biggest data breaches of the 21st century all happened during the past 11 years.

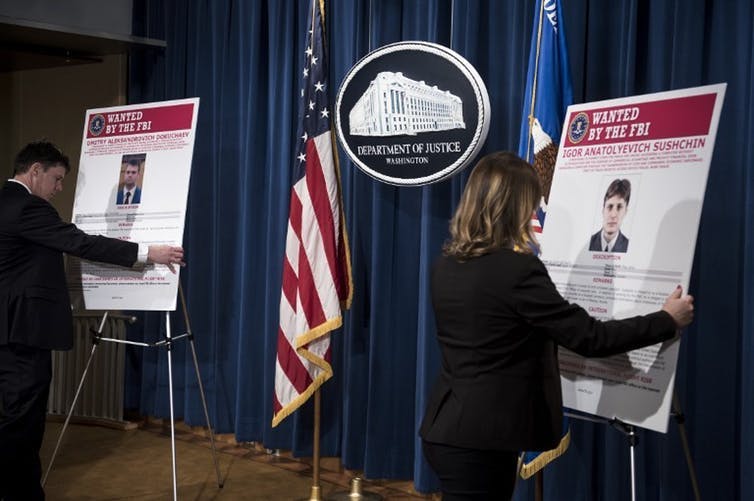

At the top of the list is Yahoo. In September 2016 the company announced that it had been the victim of a huge data breach in 2014 – names, e-mail addresses and other data belonging to half a billion users were hacked. The following December Yahoo revised their estimate, and said that 1 billion accounts were hacked in 2013. In addition to names and passwords, users’ security questions and answers were also compromised.

U.S. Department of Justice employees display posters of two Russian hackers being sought in connection with the Yahoo data breach (March 15, 2017). Brendan Smialowski/AFP

In October of 2017, Yahoo yet again revised their estimation of the number of compromised accounts. Instead, it was actually 3 billion.

Fighting a new threat model

In a research project that I am leading, we are aiming at providing cloud data security and privacy protection under a new threat model that more accurately reflects the open, heterogeneous and distributed nature of the cloud environment. This model assumes that cloud servers, which store and process users’ data, are not to be trusted to keep users’ data and the processing results confidential, or even to enforce access limitations correctly. This is a radical departure from the traditional threat model for closed enterprise IT systems, which assume that servers can be trusted.

The central approach of our research is thus to embed protection mechanisms, such as encryption and authentication, into the data itself. In this way, data security and privacy remain even if the cloud itself is compromised, all while enabling authorised to access and process shared data.

Protecting the data and its users

In our research project, we have created a suite of techniques for scalable access control and computation of encrypted data in the cloud. We also built an attribute-based secure messaging system as a proof-of-concept prototype. The system is designed to provide end-to-end confidentiality for enterprise users, and is built on the assumption that the cloud itself doesn’t necessarily keep users’ messages confidential.

To understand how it works, imagine that you’re depositing valuables in a house to which you have a key and that, from time to time, you want move these valuables to other friends’ houses where unknown people may come and go. Each of your friends keeps his or her key, but not all have the same access privileges: their keys can only open certain houses based on the access they have. Such privileges and key sets are managed by a keymaster who stays elsewhere.

Every user in the system has a set of attributes that specifies his or her privileges to receive and decrypt messages. For example, Alice’s set of attributes could be student, school of business

while Bob’s are student, school of information systems

. At the user registration stage, the keymaster issues each person a decryption code based his or her attributes.

To send a message securely, a user encrypts it, and the appropriate access policy is attached. The encrypted message is referred to as ciphertext. Only users whose attributes match a message’s access policy can receive and decrypt it. For example, if a message is to all students

, then both Alice and Bob can receive and decrypt it. On the other hand, if another message’s access policy is business-school students

, only those students (meaning Alice but not Bob) can receive and decrypt it.

The system is highly efficient – only one message is generated and delivered regardless of the number of recipients, and it achieves confidentiality even if the cloud-based messaging server and the communication networks are open.

Our system has elicited significant interest, and we’re hopeful that it can help people using cloud storage and computing in a more secure manner.