Quentin GisserotAXA Emerging Customers

September 25, 2017

They emigrate to support their families: we want to insure them

6 minutes

For low and middle-income populations in emerging countries, raising the living standards of their families is a daily struggle. Among these emerging customers, some choose to emigrate. They leave for periods of five, ten, or even twenty years, to live in a country where they can earn sufficient wages to support their loved ones back home. However, due to a lack of insurance products adapted to suit their needs, this system of family support has a fragile basis, which is threatened by life-changing accidents…

Abdul is fifty years old. Born in the city of Kozhikode (Calicut) in the Kerala region, he now lives in Saudi Arabia. Twenty-four years ago, he made the decision to leave his homeland to find work in the Persian Gulf so that he could financially support his family. Gaining employment as a factory worker for a large automobile manufacturer in Riyadh, he receives a monthly salary of 2,500 riyals (about 660 US dollars). From his earnings he sends 1,000 riyals (about 260 dollars) via bank transfer to his wife Assina who continues to live in Kozhikode.

Every year, many Keralites like Abdul decide to emigrate to the Persian Gulf to support their loved ones. It is estimated that these migrants today number several million, making this one of the world’s largest money transfer routes. The employment available in Dubai, Abu Dhabi or Doha for example, allows migrants to earn much higher wages than in India. For many, such expatriation is a sacrifice, but it is also a duty, to ensure the future of their family.

Michal Matul

Former Senior Advisor at AXA Emerging Customers

By working in the Gulf, migrants have the opportunity to earn between three to five times more money than if they remained in their homeland, and in addition they have the security of a regular income.

Long-term thinking

This financial stability enables economic migrants to plan for the future. One of the characteristics of emerging customers is that they have to make financial decisions on a day-to-day basis, prioritizing their most urgent needs. However, once a family member emigrates, the family is able to think more long term and can consider strategies to help them move towards the middle class,

Matul added. The money collected by families is used to finance their children’s education, to build a family home, or to invest in their own businesses.

Each month, Assina, Abdul’s wife, therefore receives an average of 17,000 rupees, about 260 dollars. This money is directly sent to her account via bank transfer. Assina also works: she is a weaver, but through this she earns only a fraction of her husband’s salary – a few thousand rupees at most. As for most families in the region, it is her, the mother in the family, who holds the purse strings. She saves about one third of the money received from Riyadh.

Significant risks on both sides of the corridor

However, life in such circumstances can be a delicate balance. In the Gulf countries, economic migrants are generally employed in jobs that require a great deal of physical exertion, where they may be exposed to multiple risks: occupational injuries, illness, loss of employment... These situations, which can lead to a temporary loss of income, may rapidly trigger negative impacts on the daily lives of their relatives.

What happens if the migrant is no longer able to transfer money for a given period of time? How can his family compensate for this loss of income on which it relies every month? There is clearly an urgent need to make insurance available to economic migrants.

Families that remain in India also face risks, especially regarding health, which are an inescapable aspect of everyday life for emerging customers. These risks are partially covered by the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), or the National Health Insurance Program. Launched in 2007 through a Ministry of Health initiative, this scheme provides health insurance to workers living below the poverty line and up to four of a worker’s family members. While this program constitutes a first step in terms of protection, the coverage remains limited: maximum compensation is 30,000 rupees per year, per family, which is less than 480 US dollars. This is insufficient for patients suffering from certain serious illnesses, the treatment of which can cost several hundred thousand rupees. Furthermore, in between the 20% of families eligible for the RSBY and the 10% richest who have access to traditional insurance, there remains a large segment of the population that does not have a safety net.

Given this lack of insurance, when health-related emergencies occur, families usually ask the parent working abroad to transfer larger sums of money.

Focus groups for the identification of insurance needs

In light of these risks, the AXA Emerging Customers teams decided to work on developing a package to insure economic migrants and their families. The corridor between the United Arab Emirates and Kerala was a natural choice: not only due to the size of the market, but also because of the presence of AXA in India and the Gulf countries,

explained Garance Wattez-Richard.

How can the needs of these populations be met, taking into account their specificities and lifestyles? In the summer of 2017, AXA Emerging Customers set up focus groups targeting economic migrants working in the Emirates and their families in India, with the aim of gaining an insight into their requirements and to design specifically tailored products. In practical terms, this task involved bringing together groups of 6 to 8 people and allowing them to discuss issues related to the daily lives and habits of their communities.

These focus groups are a key parameter in our research work,

explained Quentin Gisserot, Project Manager at AXA Emerging Customers, who took part in the discussions in Kerala. To obtain a really thorough understanding of the field, you can’t just sit in Paris trying to think of solutions: visiting the area is essential, to connect with the people who live there.

Encouraging free and unhindered discussion

The main objective of these focus groups was to gain a better understanding of the complexity of the lives of these populations. We limited our input to allow free and unhindered discussion between our interlocutors,

said Michal Matul who supervised the talks in the United Arab Emirates.

These meetings provided valuable insights, particularly regarding the imperative of sending money to families, the predominance of women in the role of managing the family budget, and the objectives of economic migrants. Through our discussions with these people who have chosen to leave their homeland, we have learned that they have high aspirations. These include educating their children to enable them to have a higher standard of living,

explained Michal Matul. In the Kerala region, education represents the second largest area of expenditure of funds derived from remittances, with food being the main one.

Preference for digital solutions

The second objective of the focus groups was to assess a series of insurance concepts with the participants, and to work with them to design the most suitable product in a spirit of co-creation. Several solutions were presented, with different types of coverage, price levels, and underwriting mechanisms. Over the course of the sessions, the teams on site were able to draw up the outlines of packages that met the expectations of the various stakeholders: a life insurance product for the expatriate, and health insurance that provides the necessary cover for the family.

We also noted that one of the first criteria considered by the participants was the product’s accessibility. For many, accessibility was considered as more important than the price, which is nevertheless a central issue. We found that families in Kerala had a real appetite for a digital solution that would enable the insurance product to be directly included in the money transfer mechanism. This preference stems from the distrust felt by these populations towards insurance agents in India,

said Quentin Gisserot. This solution would, however, require a period of adaptation because the focus groups involving economic migrants revealed a preference for cash transactions.

To design the right insurance product for economic migrants, the AXA Emerging Customers teams strongly believe in the need to join forces with a partner specializing in money transfers. This has a dual objective: to benefit from the expertise and trust capital of an expert in the sector, but also to encourage the growing trend among emerging customers towards opening bank accounts. Informal cash transfers remain popular as they are faster and cheaper than bank transfers, even though banks have lowered their commission charges. But such transfers are risky,

explained Michal Matul. The Indian government’s demonetization campaign has had an impact on these unofficial transfers, but they are still significant in the region.

A global problem

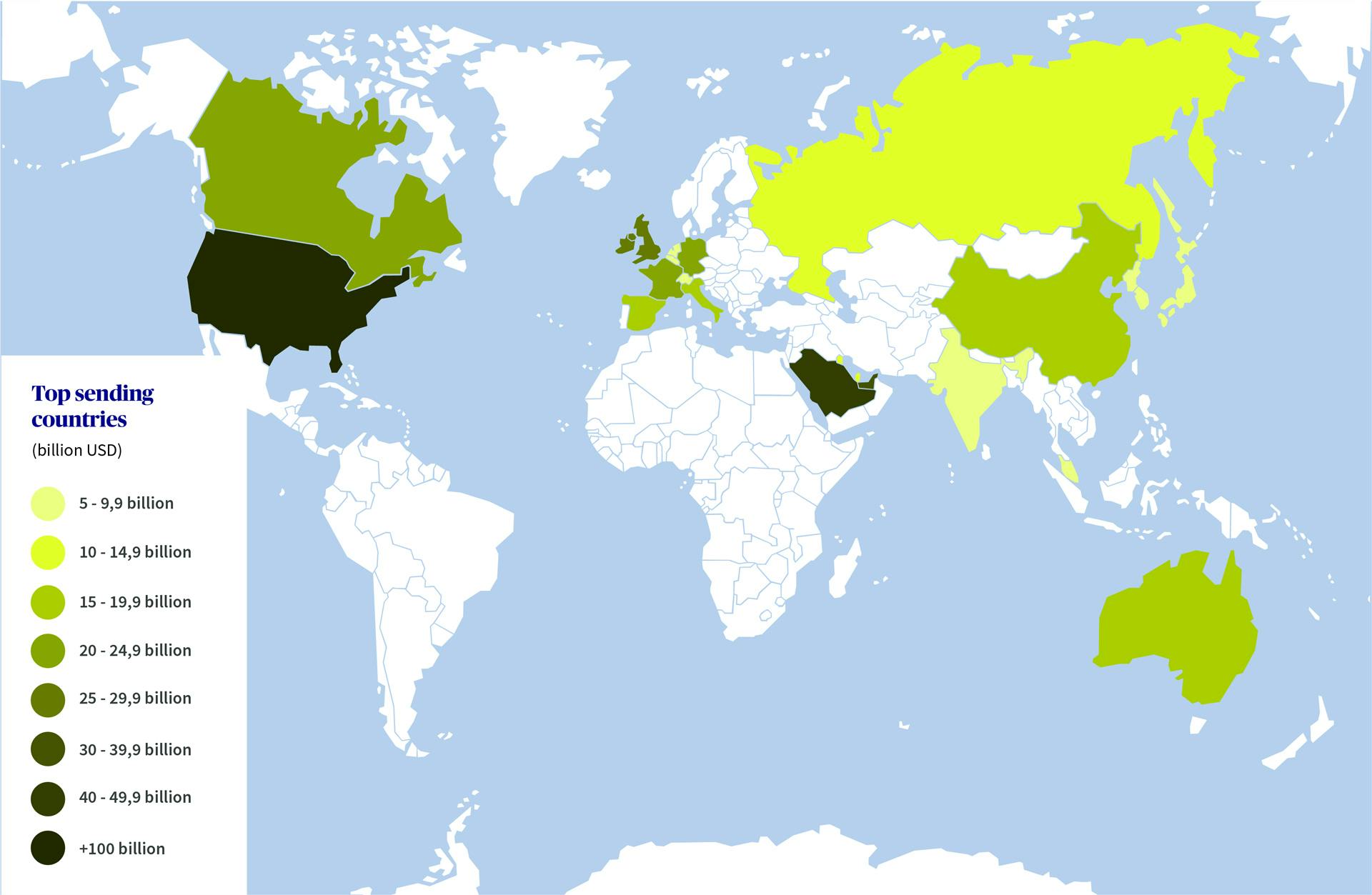

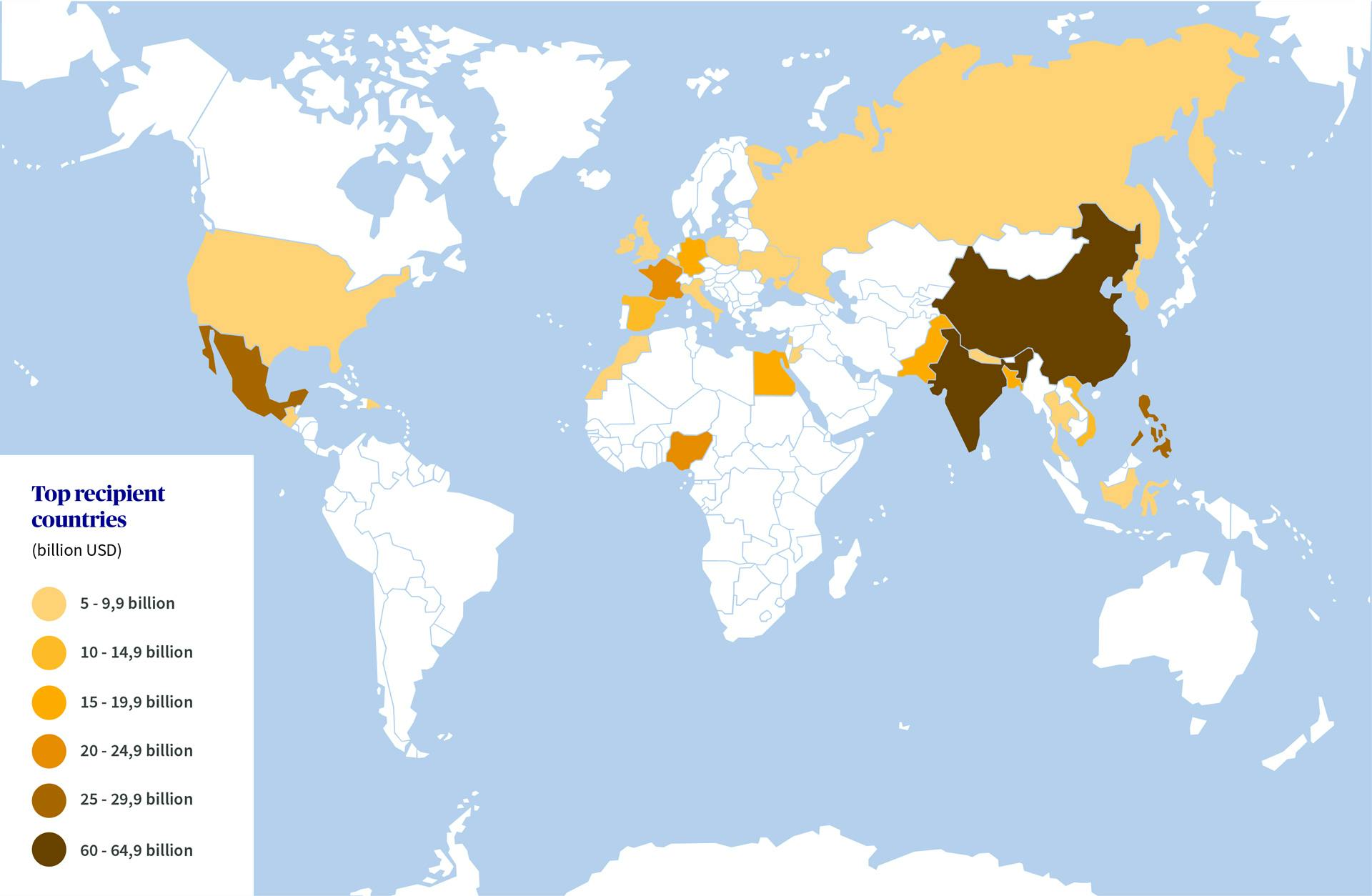

Although this corridor linking the Arabian Peninsula to India is one of the largest in terms of capital flows, it is far from being the only location where the impact of economic migration means that there is a need for appropriate solutions to be implemented. Across the world, diversifying income streams is one of the main characteristics of emerging customers. Migrants who leave to work abroad and send regular remittances to their families represent one of the most important sources of complementary income,

said Garance Wattez-Richard. The data show the growing importance of this market, which is currently undergoing major expansion: in 1995, economic migrants were responsible for barely more than 100 billion dollars of remittances; by 2015 this figure had reached nearly 350 billion.